“If you want a movement, you have to sacrifice”

ES / EN

LACE celebrates the life of our friend and collaborator, Diane Rodriguez, who passed away on April 10, 2020. In homage to Diane, we are featuring her powerful testimony that focuses on her experience with El Teatro Campesino. Additionally, she shared insights about how to create a social movement, and her recent compelling play, The Sweetheart Deal that delves into the personal challenges of being part of a collective effort of social change.

Diane Rodriguez, was a director, producer, writer, theater actress and activist. Her long term dedication to theater and advocacy to Latinx community resonates in times of uprisings, her unique feminist perspective and collective spirit was an important guide for the exhibition El Teatro Campesino (1965-1975) presented at LACE in the summer of 2017.

Thank you Diane Rodriguez for your legacy of art and advocacy!

Diane Rodriguez met with curators Samantha Gregg and Daniela Lieja Quintanar on January 28, 2017 to share her story for the exhibition El Teatro Campesino (1965-1975)

Samantha Gregg: As an introductory question, how did you start with El Teatro Campesino and what was your first experience with Luis Valdez [director of El Teatro Campesino]?

Diane Rodriguez: Well, I’m from San Jose which is a very important fact because Luis is also from San Jose. He was a migrant worker, and his family were migrants and so was my mother’s family. Santa Clara Valley was a place where a lot of California migrant workers eventually landed. My mom did the migrant trail, her family was from Coachella, they worked in all of the garlic fields. They picked strawberries, they did everything in California. And when they finally landed in San Jose in the 40’s, my grandmother, who’s a long time widow, had nine kids. They met a Filipino farmer named John Ibarra, and he fell in love with my mom’s oldest sister and they married. He then gave my grandmother and all the kids a house and they settled in San Jose. They eventually settled in Japantown in a house on 5th Street and that’s an important fact also because they were there during the internment. The intersection of the history in California that Luis has written about, and that my family has experienced, is really the core of all of the youth that belong to the Chicano Movement. Luis is not a baby boomer, he was a generation before, I am a baby boomer. I was born in the 1950’s so it was a different experience.

I came from a performing family. My father was a singer, he tried to have a career here in Los Angeles, and I think he was well on his way, but he didn’t like that life. He knew my mom’s brother, who was in the seminary school in Boyle Heights in East L.A. They became friends and he met my mother through my uncle and eventually went up to San Jose and married her. My dad was a crooner. He sang in English and he sang at the Beverly Hills Hotel. His mentor was a man named Hernando Courtright, who used to own the Beverly Hills Hotel. So, my father was very well positioned and had a great personality but he decided not to become an entertainer. However, he never stopped singing nor did my uncle and aunt, who had a quartet.

I have been in church plays since I was a little girl and performed in countless productions before I became a professional, when I was still a teenager. I say all that because, when Cesar [Chavez] was organizing in Delano, my uncle was in San Jose, who had his own business, was very middle class, had two Mercedes parked in their driveway, and watched Cesar organizing on television. He kept telling my aunt “you know, those are my people, those are OUR people.” He convinced my aunt to close up their house and go to volunteer for the UFW [United Farm Workers] and work for their paper, El Malcriado. They took my four cousins with them, this was around 1970. They stayed for about two years, and my cousins were raised in that environment. So the first time I saw El Teatro Campesino perform, my cousins were in it. They were musicians and one of them is an actor. I thought, “oh, okay. This is what the family does.”

I went to University of California, Santa Barbara and I graduated from college. I had two options. I applied for graduate school at Cal Arts and I didn’t get in. So, I went to the Teatro and I stayed there for about 11 years. That’s how I started!

SG: Can you describe the climate of the troupe when you got there?

DR: I was still in college and in the summers I would work as an intern and didn’t get paid. They put me up and fed me. I started when I was a teenager and I just kept going in the summers. If you just showed up, you were put to work and made to feel like you belong and they needed you. That feeling that they needed you was so important, and I think that’s really where the union also made you feel like, “We need you. Come and volunteer.” When a movement does that, I think it grows. That feeling of just show up, come, we will put you to work, and you’ll feel like you are doing something.

Every summer I’d go, and that’s where I did my first show. I don’t even remember what it was, just a little part in a show. And then the second summer, I was part of a bigger show. It was exciting. There was always an audience there, and at that time, they were at a garden in San Juan Bautista, called the Jardines of San Juan. It was an old melodrama house. Super tiny, there was more space on the outside than there was on the inside, but they did performances in the little theatre and also it had a screening room with a film projector. It was just a great environment. You were there in the summer, outdoors usually, people were always visiting and it felt urgent and it felt important. Luis was always welcoming and always inspiring, so, you had a leader who inspired you, and you wanted to be there, and you wanted to work, and you wanted to follow that vision that everyone else was following.

At that time, there were a lot of people who had been in college, some had stayed, and some like me had graduated. But a lot of them felt like “ughhh, I’m at UC Berkeley and I want to major in Theatre and this is not happening.” Like my husband, two years after he left Berkeley, he was in Paris with Peter Brook, it was the best reason to leave school!

I think there was a kind of energy that we always talked about in San Juan. San Juan is on the San Andreas Fault and when you go there, you see it. The mission [Mission San Juan Bautista] is up here, and then there is almost like a drop and there is the stream where there is a crack on the earth, where the actual fault is and then it springs and there are willow trees and all this vegetation and you see it, there is just energy. San Juan Bautista has the largest California Missions there is an energy that continues to be there.

SG: Who made up the audience that would attend the performances? Was it a regular audience? Was it the same kind of people showing up? Was there conversation between the performers and the audience or was there a kind of dialogue?

DR: In those days, the audience were Chicanos, but also a lot of locals from Santa Cruz, Watsonville, Hollister, Salinas, Castroville, and Monterey. It was a really great area that was semi-rural. I mean It was rural, but had all these towns around it that were not as rural, it really had an advantage. At that time you really felt that the audience was an extension of your family because everyone was of the same class, it was a homogeneous group of Chicanos. We all shared a very similar history, either it was migrant workers, or cannery workers, like people who made cans or were around the industry of agriculture. You know that is a generalization, but it is pretty true. I married a guy who is from Hollister, his family were all not migrant workers, they were cannery workers. My mother worked cannery, and if you talked to anybody of that generation, most women worked at cannery at some point in their life before they got trained to do something else. It felt like you really knew your audience because they were like your family, they had the same values as your family. It is harder now to do work because it is different, in California now there are a lot of Mexicans who were raised in Mexico who have more of the Mexican value and they do not have the same history as we do. It is harder to find that audience that will relate completely, although they are coming out for Zoot Suit.

Daniela Lieja Quintanar (DLQ): Can you explain or tell us more about your experience in the different sites where the Teatro was doing the actos? like the fields or the union halls.

DR: Luis Valdez belonged to the union and actively worked in it, for only about two and a half, maximum three years when he was under the umbrella of the Farm Workers Union. He then subsequently went to Del Rey, California, which I think was in 1967, really only two years later, he still had a strong relationship with Cesar, but he was no longer under the umbrella of the UFW. The work changed, he [Luis] started doing actos about students and chicano militants, etc. By the time he moved to San Juan Bautista in 1973, he was doing longer theatrical pieces, and the actos were something we did when necessary. By ‘73, ‘74, ‘75, ‘76 we were writing actos that were not necessarily about the farmworkers. We would write about propositions that were happening. However, we would go back on occasion, and on many occasions, I am not saying we did not, in which we were going back to help with the strike in a certain year. By the time the 1970s came around the growers were not happy with the presence of the UFW organizing the farmworkers. You would go on the property on the ranch and the growers would literally come with shotguns and ask you to get off. Sometimes it was hard to perform the actos on the ranches because the growers would immediately come. There were court injunctions already in place. In the early days, growers did not know what the hell was happening, so the Teatro was able to get closer to the worker and then there were the union halls and the hiring halls that they were able to actually perform their work.

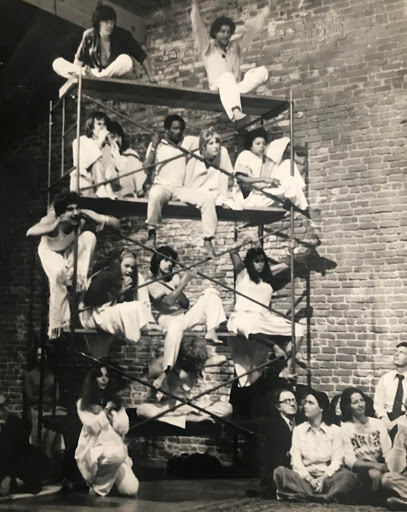

It seemed to be easier to perform at rallies, because you would be on a stage many times and perform the sketch in front of microphones. Performances were always on mic, we were very loud, but you had three mics and you would try to perform in front of them. There was obviously no set, just a mask and signs you had to be fairly broad. Oh my god, it took me years to stop over-acting. I was horrible! I was really a terrible actor, but it was good for those [type of characters]. J.D. my husband was a very good actor at twenty two. I became a very good actor at thirty five. Some people are different. People like my husband, Jose, J.D., and people like Socorro Valdez were the masters of the performance. They just knew how to do it, with craft and broadness but without over-acting. They were deeper in their craft. Basically, performing near a ranch was nearly impossible at a certain time in the 1970s because of the injunctions. Most of the performances happened at rallies or halls, and many times Cesar would be in the audience. He would always be in the front row, and he would always crack up. I think he was the best audience ever. He loved the humor and he was always around a lot of those performances. They really worked. They really educated the worker on the issue of the day just by these simple sketches. That is how it related to the farm workers issue by the time we started creating larger pieces that were about campesinos, but they had a certain aesthetic. We had already crossed the threshold of being contemporary theater artists. There was really no other Chicano theater, and really no other Latino theater company in the United States that made that cross over. And now that I work in contemporary theater, I see that the festivals in Europe in which we made really our world class reputation were obviously interested in the subject matter, which were farm workers but also in the aesthetics which was physical and it kind of pushed us through to a whole different kind of audience.

DLQ: What was your personal daily experience with the Chicano resistance, with the movement?

DR: It was completely around the theater. I have to say that because we were a very disciplined company, I never had a chance to do anything else but theater with el Teatro. We wake up early and we would do a couple of hours of workouts. Luis was experimenting with an idea of what is called theater of the sphere. It is a way of a performer feeling circular, like a ball. We experimented with just a lot of Nahuatl thought and culture, Mayan numbers, the notion of hell, which is Mayan zero, when you perform you are empty and full at the same time. That contradiction as a performer you need, you know you are dead and alive. We had a philosophy that we tried to physicalize through exercise in the mornings, in the afternoon we would probably do a rehearsal and at night there was always some kind of study whether it was Mao Tse or whether it was Marxism. We would read, we learned Aztec poetry, we learned how to recite it in three different languages. It was like a masters program, it was a Ph.D. program for a dozen years.

DLQ: How did the Chicano Movement in California, the one here in Los Angeles, impact the work you were doing together?

DR: We lived in San Juan, which is great because we were isolated and could create. We went to the TENAZ festival in 1974. We were very controversial. Alma Martinez documented that festival in her P.h.d. From the quiet of a small town, we would go to Mexico City and the Marxists tore it apart. I mean, it’s got Christian symbols in it and it was like the center of controversy. So we pulled back and created another show. From the quiet of a small town to the roar of large cities, we would find ourselves in it. And some people were completely inspired by the work and others were distracted, so you really never knew. That is when we would go to festivals.

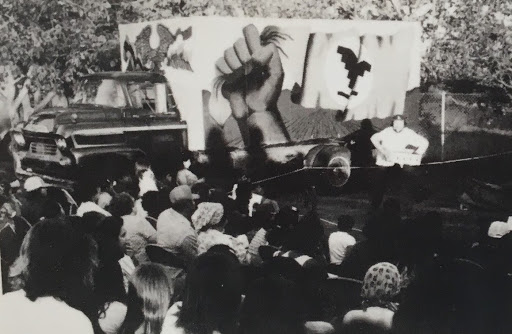

When we would perform on the road, we would usually stay with people and then do a couple of performances, one in the theater, and one in the neighborhood. I remember being in Texas, and being on trucks with loud speakers going through the barrios announcing that we were going to be there and it worked. I remember we were in a place called San Juan, Texas, which is in the Rio Grande Valley, and we performed in a backyard of a UFW office on brown dirt, soft beautiful brown dirt. But then you were filthy. And then, that night we would go to this small town and there were no lights, so we literally performed with headlights. This was all in a really, really poor area in Texas. Then, the next moment, we would be on a plane and we would go to a wealthy community in Connecticut at the White Barn Theatre, a woman named Lucille Lortel owned it, and there was a luncheon that we had to attend. We had just flown in from Mexico and the last thing I remember was sleeping on tobacco leaves and then we are on this plane from Texas to Connecticut and we go to the White Barn theatre for a luncheon, and it is outdoors and all these ladies in hats and it is the Teatro Campesino. And we were performing the same show that we performed in Mexico City and the culture shock. We stayed with one of the editors of The New Yorker, who was super nice and super cool.

At that time people saw us as this movement that was exciting and bohemian. Rich people would host you, and poor people would also host you. We had very radical hospitality on either end. At that moment we were on a beautiful lawn, I see on a hill these guys coming down, one wearing a huge sombrero, and it is Miguel Piñero! We used to call him Pancho God, he was a director, and he came to see the Teatro and said, “Teatro, man, teatro!” And again these were like almost gangsters that the rich people just thought they were artists. Miguel had just done Short Eyes on Broadway. This is kind of a really weird combination of things. It was radical where we performed. The very different stages, from flatbed trucks to greco-roman theatres in Sicily that was the range and everything in between.

SG: And the smaller towns like the one you mentioned, like in San Juan, Texas, that were organized in conjunction with United Farm Workers?

DR: That was all independently done. By the time Luis left in 1967, it was an independent theatre company. There was a relationship with el Teatro and the UFW, but there was no longer any oversight from the UFW, which was better.

SG: You also talked about the kind of different resources you were using when you were working at, or preparing for performances. Were you also actively viewing plays by other troupes or looking at theatre or at specific actors or troupes in reference to developing actos or styles of performing?

DR: Luis had been with the San Francisco Mime troupe, and I think they were our biggest influences. There was a comedia del arte aesthetic, there was broadness, there was performing outdoors, and he brought all of that knowledge to the Teatro. He started the troupe in 1965, by 1973 Peter Brook had come into the lives of el Teatro with his whole troupe and I think that we were able to see a quality of actor that we could aspire to, and also a way of life that was embracing our whole day. Peter Brook had the Institute of International Theatre Research and he had a group of international artists that traveled and toured with him all over Africa. They came to the U.S. and after us, they went somewhere in the Midwest. It was very inspiring to see the dedication and discipline these actors had that then influenced us in the next half of the decade, in which I think our work was the strongest and most international because we were really aspiring towards a very big aesthetic and discipline. Malcolm Gladwell wrote a book about when you become an expert in a field, there is about ten thousand hours that you put into the work. I think that is where I put my ten thousand hours, as a theatre maker, starting off very broadly and then refining the craft until we left. It took that kind of dedication, from morning until night, to complete submerge. Which, people cannot afford to do anymore. It is hard to have a company. People accuse you of being a cult, which we were often accused of.

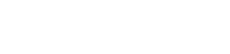

SG: What was the size of the troupe when you started?

DR: It averaged around thirteen people [that] we would take on the road. I always remember that number. But at home there were spouses and a lot of people did not travel because they had kids. At home we would make shows, and there would be bigger casts, and there were always community people involved. That notion of engagement, we would just do that naturally, and you would have people from the community that were in our shows and looked like they were professionals. You do not have to sacrifice excellence when you have someone from the community, because so many of our people were community actors. When there is passion and discipline, you just know how to carve it out so that they look good in what they can do. There was an exercise I would always do with the young artists, which is this notion of do what you can do, say what you can do first, and then do what you can do, and it is very hard. Because people all want to do more, and you cannot do that, you can only lift your arm this high, that is all you are going to do and you are going to lift it expertly. I think the troupe could have been twenty-five people but on the road, the maximum we ever took was about thirteen including musicians.

DLQ: You being a woman in this troupe, in that moment, how were your feelings about that? Especially when there have been critics about patriarchal models, now has been more developed in different ways? How was your experience in Teatro Campesino being a woman and now in your long career in theatre?

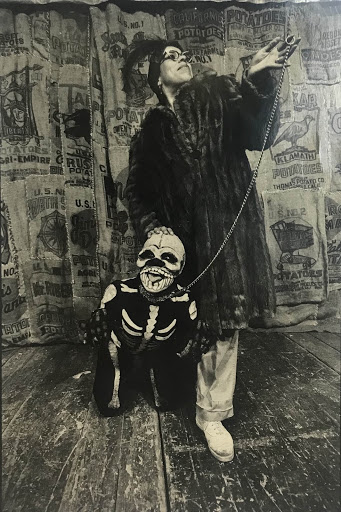

DR: First of all you have to understand, that the most important thing is that we were all pretty opinionated. And I would say, there was myself, there was Socorro Valdez, who was Luis’s youngest sister, and there was a woman named Olivia Chumacero, who is still in town here. We were primarily the woman that would go on the road. There was a woman named Lily (Liliana) Alvarez who was very strong willed. The women were…very, very strong. We never shut up. We would fight. I mean, it was led by Luis. And no matter how loud we were at that time, it was about the man that led it. And clearly he had started it, it was his company. There was no way around that. We were there because of him, and because he had an amazing vision. In a way there was a story to be told. And at that moment, it was not our story. It was the story of a people. We gather around to tell the story of our people. Now I have the opportunity of telling the story of our people, through a woman’s perspective and that is what I am doing now. But then, we had a bigger goal. It was not so much a bigger goal we had. We had a goal that seemed to be about positioning us as a valid member of the society. That was clearly the issue, but the roles were not great. They just weren’t. I loved playing the androgynous [characters]. there were a lot of androgynous characters to play, and so that is what I did. I played la Muerte. I played the Diablo. A Calavera, which then you were dressed in full calavera, from head to toe. You could play a man or a woman, whatever. It was so fun, it was so liberating. We all had fun doing that. Noo! I never played la Virgen. That was more reserved for a more dainty actor. Socorro, nor I, or Olivia ever played her. We were the ones that were always on the road. We were the ones that had a kind of muscle that could play a huge range of types of characters, that then freed us and so we found our freedom within the structure. And I very rarely played the suffering mother. There was a woman, Adela Gonzalez, who was a beautiful, beautiful young woman in her twenties. Her parents were Mexican, she is Chicana, but her Spanish was beautiful and she always would play those mothers. I was just so admiring of her, but I could never do that. I was bigger. I was broader. I was more brash. I was a whole other deal. I was never that fine.

DLQ: Did you collaborate with other theater and activist groups that were around that time these other groups that you were mentioning, Teatro de la Gente and how was the relationship?

DR: I have to say it was not bad, but there was a competition. Luis had started with the whole Chicano Movement, so we were the competition, and we always got the attention, but other groups thought they were better. Every year, we would go to a TENAZ festival, and we would all be together. It was very collegial and it was great, but there was a little resentment about the Teatro getting so much attention. I do not ever remember really doing a collaboration with Teatro de la Gente, although they were our neighbors. My cousin, Ed Robledo was in el Teatro de la Gente and he was also a musician with us. We were aware, and of course we knew each other.

TENAZ festival was an alliance of Chicano and international theater companies based in the United States. Every summer, we would go to festivals and we would show our work and there would be workshops. It was fantastic. There was one in San Jose, San Antonio, Chicago. There was one in Mexico City. The one in Mexico City, everyone ended up going to Calexico and taking a train down. Hundreds of teatristas went to Mexico City on a train. Some people got stuck in second class or third class where the windows were open. It was a journey. Everyone got there and we stayed at convents, in schools on the floors, and everyone performed and workshopped every morning. We would see a show at night, and in the mornings we would discuss the work. It was a great way of coming together, but it was also a great way of seeing who is better. It was a contradiction, because we were competitors, yet, we were in a movement together. We were after the same goals and appreciated each other. It was a healthy competition.

DLQ: Can you talk about The Sweetheart Deal and what led you to your interest in writing it?

DR: I have been writing plays for about ten years. I have these three plays that I have been working on that have women at the center. And it is basically about women coming to consciousness through various different stories. I was really intrigued with the story of my aunt and uncle leaving to go volunteer at the UFW for The Malcriado (newspaper). So, they were the kernel of the story. The beginning, the impetus of that story. But then, everything else is fiction. I was also interested in telling the story of the United Farm Workers Union, but the trap and reason people have not been able to produce this story is that everyone has to tell the story of Cesar and Dolores. And, that is too complicated. I don’t want to do a story about them. I want Cesar and Dolores to be there, but I never see them. I hear them in a rally voiceover, but I never see them.

This is a story about the volunteers who made up the Union, like all of us who were everyday working in the movement but were not famous. This is about them. Their struggle. Their sacrifice. And the question of how much do you sacrifice for the greater good? Which is at the crux of my story. And at times, if you were at that cross work road where you have to turn in a family member, do you do it for the greater good? Or, if you are one of my characters, at that time there were less people with undocumented working in the fields, people called them illegals. Cesar called them illegals or wet backs. He would use those words. Organizers were forced to turn them in, because they were working as scabs, but to turn in your own people for the greater good…it still wears on you and you cannot sleep. There were sacrifices to be made for the greater good of the movement, and so these are the big issues that the characters grapple with in my play. Then you have a family where a brother and sister [are] working for different sides, breaking up families. Very true, [it] happened all the time. How do you make that work? How do you live with that? I felt that I could really grapple with a lot of issues while discussing a movement. Now, when we have to have a movement, when we are at the beginning of a movement, it just feels so necessary to talk about these things and to understand what it is to be an organizer, and the world [un]certain and sacrifice come into play and are we willing to do that as we create a resistance. So these are big questions.

DLQ: Now that you work in institutions, what are the differences you see in the Teatro Campesino in terms of the impact with community engagement and political activism? In that time and now in this time.

DR: I think they become very local, less international but very local. They have all these education programs in the summer and they are still impacting the lives of youth. This is the way they have been able to survive for fifty plus years, it is really investing in the rural area of some of San Juan Bautista, East Salinas, and all of San Bernardino County. There are a handful of theaters across the country that are doing that, and they do it well and they have three local shows that they still do, The Virgen, The Pastorela, and Day of the Dead. And, they have created this new show Popol Vuh, which is the Mayan creation myth, in which they are able to get non professionals in it and they do an amazing job. I brought them up to do it with our community here in LA at Grand Central a year ago. It was amazing, and those people were non professionals, such a good show, very big production, with people from Boyle Heights.

The big question is, and it is a broader question than just a Chicano organization or theater company, but, how do companies have longevity and sustainable leadership, and evolution to be able to continue to matter and be relevant in a world that is constantly changing? That is the bigger question. The Teatro has managed to continue to stay alive and their choice has been to only focus on the area around them. I would say that in the last 5 years, 3 years, there has been a resurgence of Latino Theater, and we have this new alliance called Latinx Commons. It is a hot group that has an open leadership platform, meaning that nobody is a leader, and we have an advisory committee that makes decisions. We have had common festivals like TENAZ, which developed new plays. We are having an encuentro at Los Angeles Theater Center (LATC) in the fall, that is part of the Latinx Commons. There has been a reemergence of Latino Theater collaborations and alliances to further contribute to the American theater narrative. The shows are not necessarily political, but this very act of doing this is a political act and the Teatro is involved in that. I find that there has been a lot of progress and even though there may not be the number of Teatros that existed in the seventies, there are many Latino artists who are politically conscious and companies that are doing work. The teatro was at the beginning of that. For me, because I was involved, I started young, and to still be very much having a career and having been able to see this, it is very rare. I feel I am at a very privileged point of a hill that I am able to see this huge trajectory. It is really exciting.

SG: This exhibition largely obviously existed in the present day and largely the project looks at Teatro as a model. As someone that was part of it, What do you think given the current contentious political climate, what can we gain by looking at something like Teatro as a model? Or What do you personally benefit from having distance from the early performances to now?

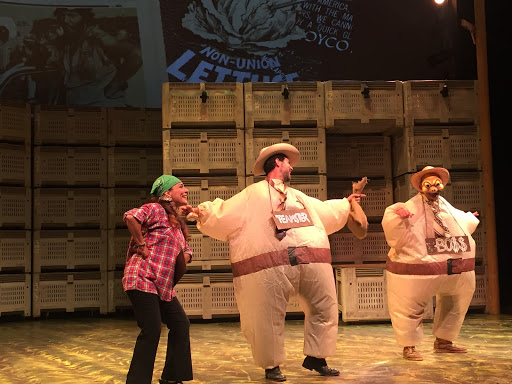

The Sweetheart Deal by Diane Rodriguez at LATC. Left to Right Linda Lopez, David Desantos, Valente Rodriguez. 2017 Courtesy of LACE.

DR: Let us talk about aesthetics. With the early aesthetics, you have this political sketch known as an acto that has certain rules. It is based on archetypes and stereotypes, that is number one. It is always a villain who is the boss. There are the signs you wear, masks, and you create a scenario around the protagonist. The antagonist will give a political message in a quick snapshot of about six to seven minutes, maybe less. That can be done with no set, just the actors bodies, their signs, and their masks or without masks. They are done in front of a large number of people or they can be done on video now, you just have to figure out how you want to get that out to the public. At the Women’s March in downtown LA, there were speakers and a huge crowd but once you got to city hall you could have had an acto. Instead of talking heads you could have had some theater and now with huge puppets it can be whatever you can almost do an acto with huge puppets. It is taking that form that is number one.

The second thing is if you want a movement, you have to sacrifice. There is just no other way, there has to be sacrifice and if the sacrifice means you are not going to make a lot of money that is the sacrifice. We were able to participate in the movement because we were at the time only getting paid 16 dollars a month and we had our housing and food taken care of. The Teatro owned a house, and that is all we made and we were being taken care of by the movement. That is the thing. You have to believe that the movement will take care of you. If you are in a company or a group of people in which people give you things, like they will house you, but it is living in poverty for a while, and I do not know if people get that. Martin Luther King, did he have a job? He did have a church he was a pastor of. Cesar Chavez, he did not have a job. Dolores Huerta, these people do not have jobs. Your job is being an organizer and it is low pay, it is that kind of thing of sacrifice. There are certain things that have to be in place in order for a movement to be created. Even if a movement is not created but there are people coming together to try to learn about issues, this model is important, and can be morphed into a more contemporary form. That is really why I was so compelled to write The Sweetheart Deal, to reintroduce the actos and to reintroduce the form as a possible way of us communicating change and making change.

Diane Rodriguez is an anthologized writer, regional theatre director and the recipient of an Obie Award in 2007. She began her career with one of the most politically explosive theatre companies of it’s era, El Teatro Campesino. In 1988, Rodriguez along with other Latinx actors, founded the theater collective Latins Anonymous as a response to Hollywood’s normalized practice of employing Latinx stereotypes in productions. Her two-play anthology, written collectively with Latins Anonymous, is in its 16th printing. As of January 2017, she will have been at Center Theatre Group for over twenty-two years and is currently Associate Artistic Director and President of the Theatre Communications Group Board. Her recent work includes the successful and critically acclaimed production of The Sweetheart Deal, which she wrote and directed, at the Los Angeles Theater Center (LATC).