This collection of archival images and texts of silent protest was curated by Eve Arballo and Tess Carota as part of the exhibition SOUND OFF: Silence + Resistance. It brings together documentation of historical and current protests, as well as critical and speculative texts about silence and resistance. While by no means an exhaustive exploration, these curators researched throughout the duration of the exhibition and added information to the vitrine over the course of the exhibition, culminating in a bibliography of sources and texts.

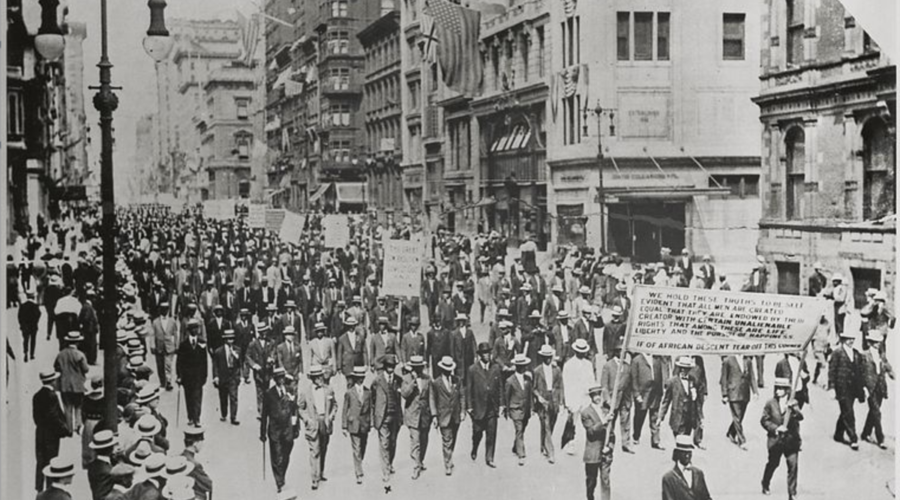

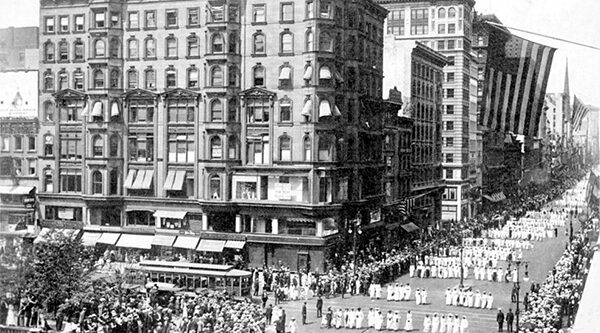

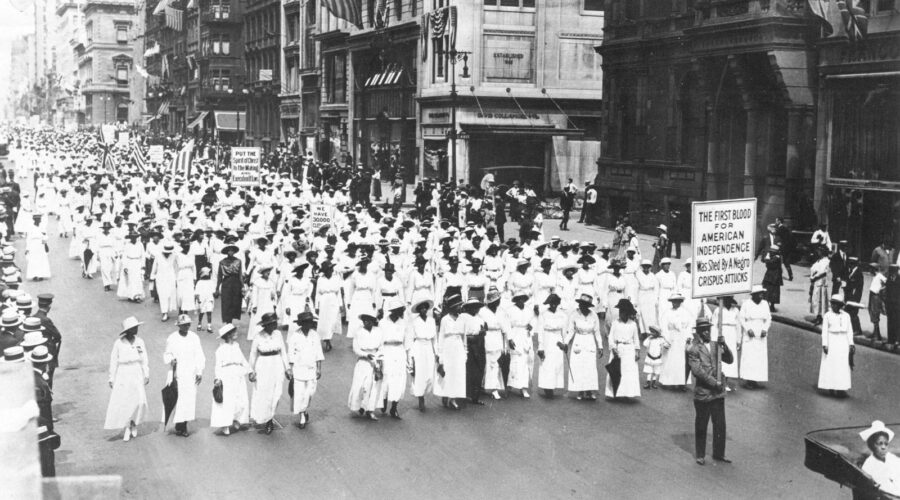

1917 Silent Parade in New York City

The summer of 1917 was rife with racial tension nationwide. After weeks of hostility and attacks on Black workers who were employed to replace striking white workers in a Bauxite processing plant, a white mob set fire to the Black section of the city on July 1, 1917. At least 39 Black residents were killed, hundreds more injured, and thousands were left without a home. In Waco, Texas and Memphis, Tennessee, the widely publicized lynchings that took place between 1916 and 1917 added to the anger and grief of Black residents across the country. The NAACP composed a retort in the form of a Silent Protest Parade to take place on July 28, 1917. On this day in New York, between 10,000 and 15,000 Black men, women, and children marched in silence down Fifth Avenue. The group walked wordlessly to the beat of a drum with raised picket signs which stated their purpose and demanded justice. Their tactic was silence, but the message rang clear: anti-Black violence is unjust and un-American. The Silent Protest Parade of 1917 was the first of its kind to take place in New York and was the second instance of Black Americans publically demonstrating for civil rights.

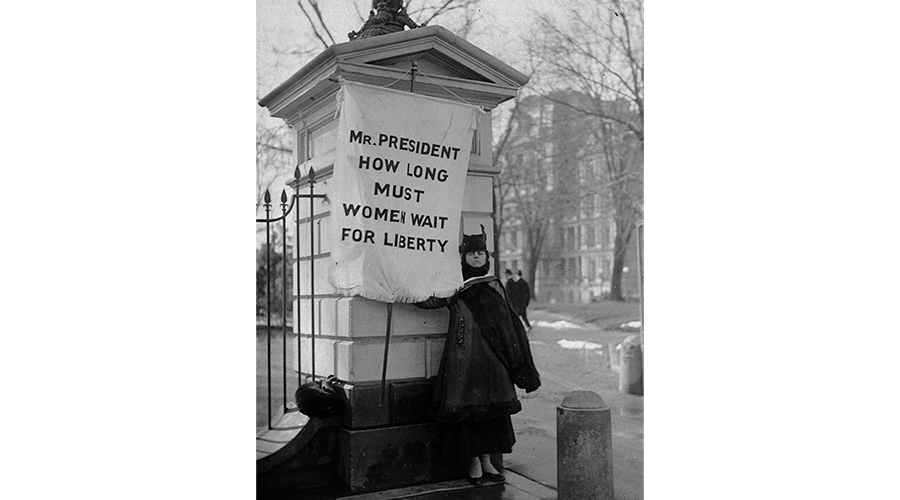

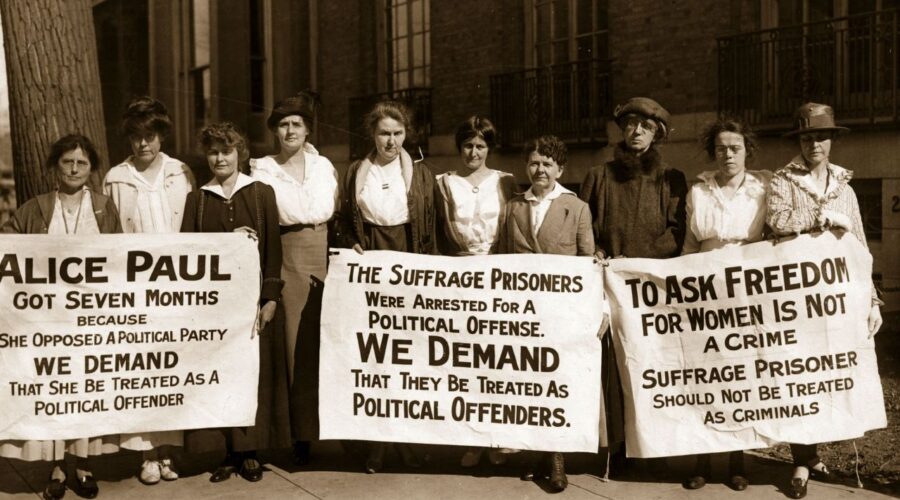

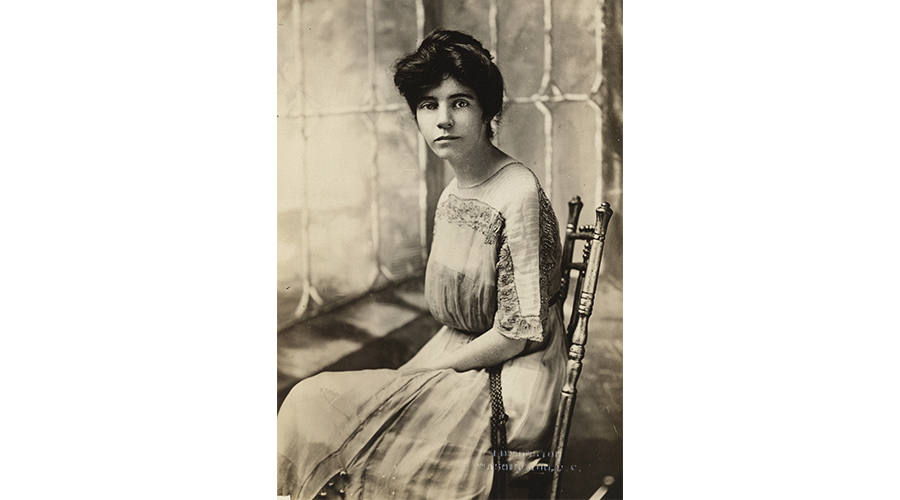

Alice Paul, Silent Sentinels

For six days a week, from January 10, 1917 to June 4, 1919, the Silent Sentinels advocated for women’s suffrage by picketing outside the White House. The Silent Sentinels, who were members of the National Woman’s Party, received their nickname for their silence while protesting. The group was led by Alice Paul, who founded the National Woman’s Party with Lucy Berns, and had been protesting for the addition of the Nineteenth Amendment since 1913. Under Alice Paul’s guidance, the Silent Sentinels were the first group to picket the White House. After an unsuccessful meeting with President Woodrow Wilson on January 9, members of the National Women’s Party stationed themselves in front of the White House, holding banners with statements that often cleverly used Wilson’s own words. While arrests and harassment of the protesters took place, the members of the NWP retained their identity as a Silent Sentinel even while in jail, often staging hunger strikes as well. As violence mounted against the women, Wilson intervened. In 1918, he publicly supported women’s suffrage for the first time, and on June 4, 1919, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed in Congress.

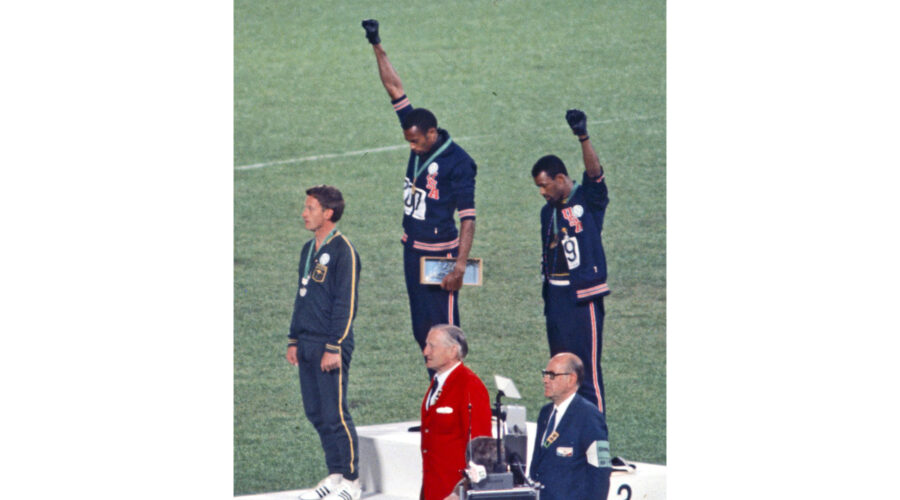

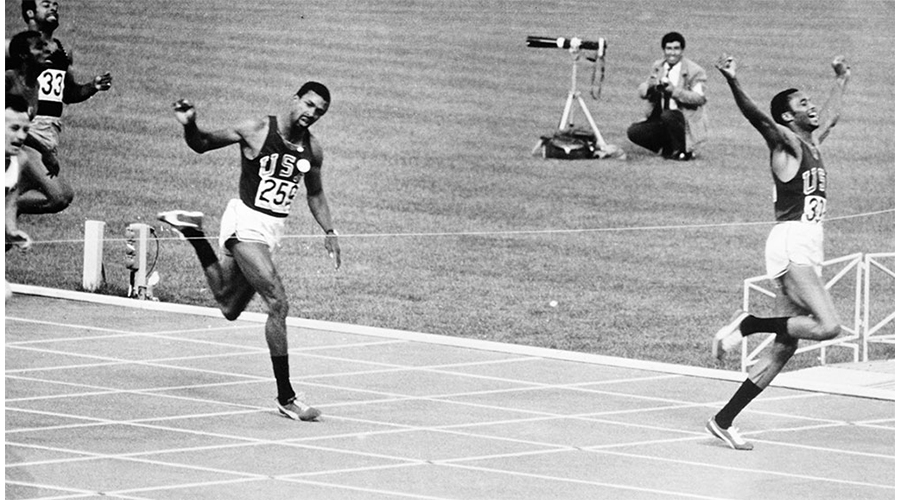

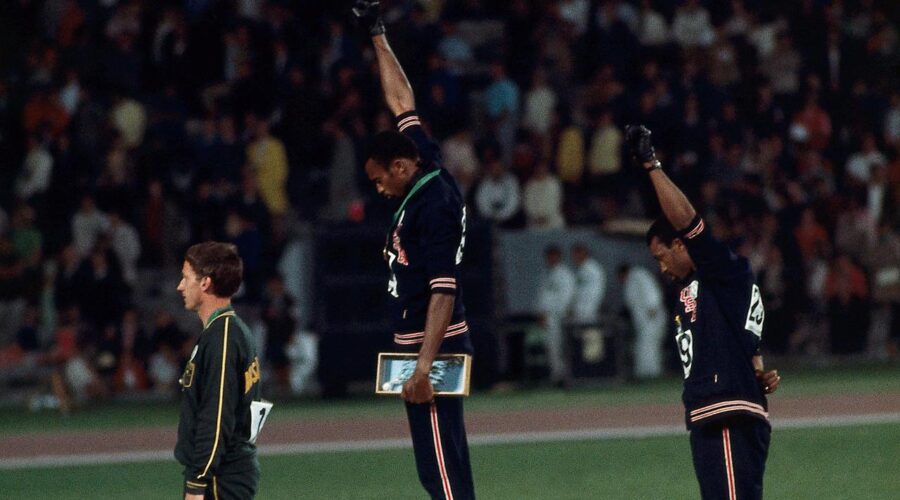

Tommie Smith and John Carlos at 1968 Olympics

At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, despite the failed attempts of the Olympic Project for Human Rights to boycott the Olympics, a series of smaller but equally powerful demonstrations took place. The Olympic Project, which was established in 1967 to protest racial segregation, included prominent athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos. After winning gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200-meter race, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised a gloved fist as the star-spangled banner played. The Australian silver medalist stood in solidarity, wearing an Olympic Project for Human Rights pin. During the anthem, Smith and Carlos also removed their shoes, which Smith later explained symbolized Black poverty, while the raised fist symbolized Black power and unity. After this silent gesture, the US Olympic committee accused Smith and Carlos of not only violating the principles of the Olympics but of taking political action against the US. Because of their refusal to comply with the committee, Smith and Carlos were suspended from participating in the games. Acknowledgments in honor of the action that Tommie Smith and John Carlos took that day range from musical tributes, a statue at their alma mater (San Jose State University), and murals in Sydney, Australia and Oakland, California.

Colin Kaepernick

On September 1, 2016, Colin Kaepernick and Eric Reid kneeled during the National Anthem to protest police brutality and racism. Two weeks prior Kapaernick had sat on the bench while the National Anthem played, catching the attention of his teammate Eric Reid. Wanting to show solidarity, Reid discussed how he could get involved with Kapaernick and use their highly visible platform as NFL players to protest police violence against Black Americans. After much consideration, the two chose to kneel, a gesture of grief in the wake of a tragedy. It was after this act that Kaepernick’s protest gained national attention. The gesture inspired over 200 NFL players to kneel in 2017.

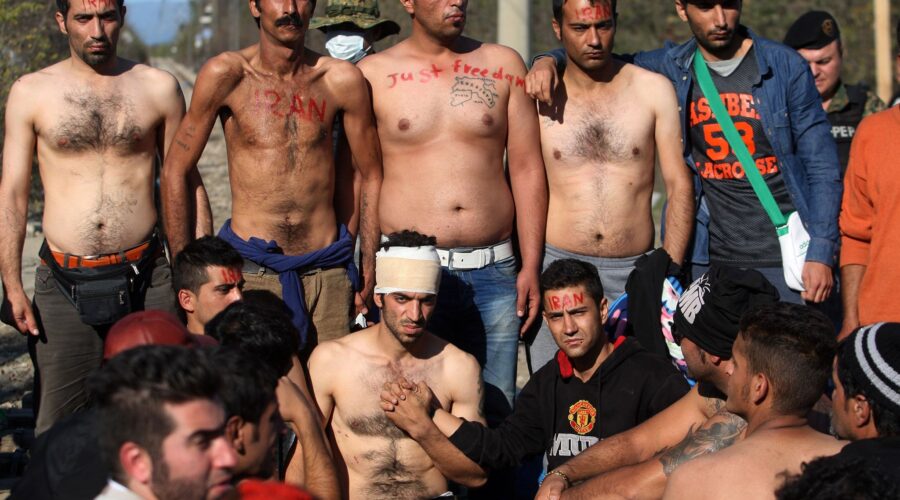

Lip sewing on Greece/Macedonia border 2015

After the Paris attacks in 2015, a wave of restrictive immigration policies were implemented in countries such as Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, and Macedonia to prevent passage to northern Europe by refugees seeking asylum. By deeming individuals from all countries except for Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan as economic migrants rather than asylum seekers, the policy trapped thousands in places such as Idomeni, Greece. In the Idomeni Refugee camp in November of 2015, at least five Iranian men sewed their mouths shut and participated in a hunger strike to protest not being allowed to complete their journey. Those at the Idomeni Refugee camp who were Moroccan, Iranian, and Pakistani were trapped in the camp in addition to being unable to return home. The five men protesting had also been camping on railroad tracks at the border of Greece and Macedonia along with others, hoping to block train lines. Shortly after, Macedonia began constructing the North Macedonia barrier, which remains intact today. The Idomeni refugee camp is the largest in Europe, and now includes mosques, schools, and businesses.

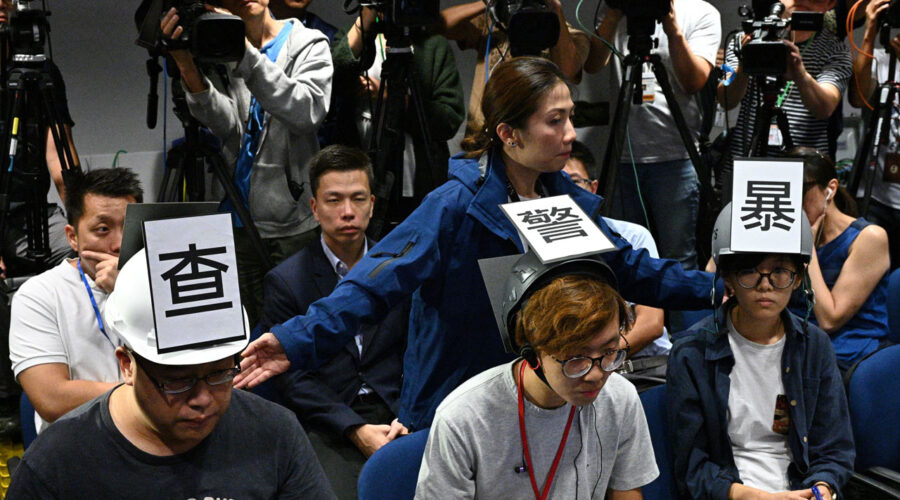

Journalists in Hong Kong

In early November of 2019, in the midst of the Hong Kong protests, six journalists sat in the front row at a weekly press conference in silence. Each of the six wore a safety helmet, a symbol of solidarity with the protesters with Chinese characters on the front combined to read “investigate police violence, stop police lies.” The journalists, acting in response to the arrest of and violence towards media staffers, ignored the repeated requests of the police to remove their helmets. After twenty minutes of not speaking, the press conference was ended entirely.

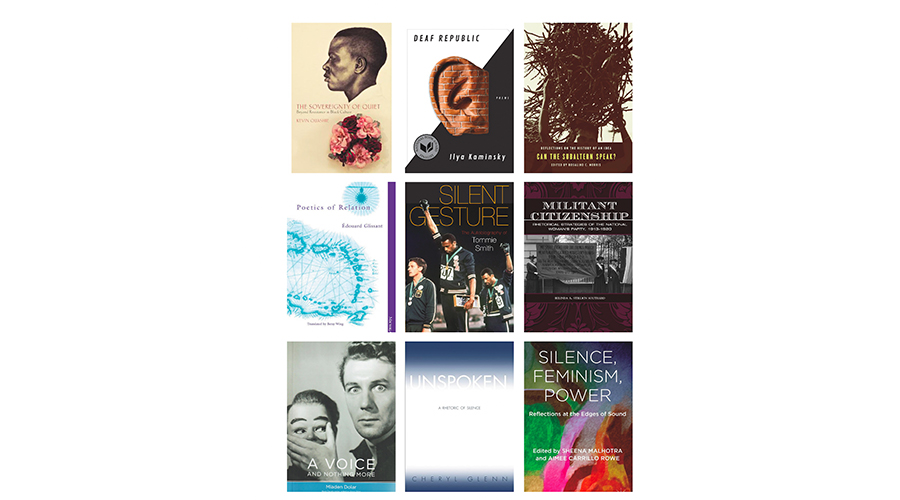

Silent Protest Bibliography-

Books:

-Achino-Loeb, Maria-Luisa. Silence: the Currency of Power New York: Berghahn Books, 2006.

-Dolar, Mladen. A voice and nothing more Boston: MIT Press, 2006.

-Fiske, Lucy. Human Rights, Refugee Protest and Immigration Detention. 1st ed. 2016. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

-Glenn, Cheryl. Unspoken: A rhetoric of silence. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

-Glissant, Édouard, and Betsy. Wing. Poetics of Relation Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

-Kolowratnik, Nina Valerie. The Language of Secret Proof: Indigenous Truth and Representation Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019.

-Malhotra, Sheena, and Aimee Carrillo Rowe, eds. Silence, feminism, power: Reflections at the edges of sound. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

-Quashie, Kevin Everod. The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

-Sim, Stuart. Manifesto for Silence: Confronting the Politics and Culture of Noise Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

-Shawcross, Harriet. Unspeakable: the Things We Cannot Say Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2019.

-Smith, Tommie, and David Steele. Silent Gesture: The Autobiography of Tommie Smith. Temple University Press, 2008.

-Spivak, Gayatri. “Can the subaltern speak?” In Marxism and the interpretation of culture, ed. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

-Stillion Southard, Belinda A. Militant Citizenship: Rhetorical Strategies of the National Woman’s Party, 1913-1920 1st ed. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011.

-Walton, Mary. A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Peer-Reviewed Articles:

-Bargu, Banu. “The Silent Exception: Hunger Striking and Lip-Sewing.” Law, Culture, and the Humanities 0, 00 (2017): 1-28.

-Dotson, Kristie. “Tracking Epistemic Violence, Tracking Practices of Silencing.” Hypatia 26, no. 2 (May, 2011): 236–257.

-Hill, Thomas E., Jr, “Symbolic Protest and Calculated Silence.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 9, no. 1 (Autumn, 1979): 83-102.

-Marie Ranjbar, A. “Silence, Silencing, and (In)Visibility: The Geopolitics of Tehran’s Silent Protests.” Hypatia 32, no. 3 (August, 2017): 609–626.

-Weitzel, Michelle D. “Audializing Migrant Bodies: Sound and Security at the Border.” Security Dialogue, 2018. doi:10.1177/0967010618795788.

Websites/News Articles:

-1917 Silent Parade in New York City

“Silent Protest Parade Centennial”:

https://www.naacp.org/silent-protest-parade-centennial/

“The Negro Silent Protest Parade”:

https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai2/forward/text4/silentprotest.pdf

1917 Suite | The NAACP’s Silent Parade:

https://blackbird.vcu.edu/v16n2/gallery/1917/silent-page.shtml

Newsreel footage:

-Tommie Smith and John Carlos at 1968 Olympics:

Original LIFE magazine article:

-Lip sewing on Greece/Macedonia border 2015

“Refugee crisis: Stranded Iranian asylum seekers sew their mouths shut in protest at Greek-Macedonian border”:

– Alice Paul, Silent Sentinels

“Alice Paul”:

https://www.nationalwomansparty.org/alice-paul

“Silent Sentinels Picket for Women’s Suffrage (1917-1919)”:

https://www.theclio.com/entry/50548

-Journalists in Hong Kong: